I've always been someone who enjoys scribbling and doodling —usually just for fun.

Abstract shapes, chaotic patterns, overlapping lines…they weren’t polished or “proper” drawings, but they filled pages quickly and kept my hands moving.

The kind of thing I’d often sketch during downtime or just to clear my head.

Recently I noticed a really cool trend starting. A series of online videos where people were committing 100 hours to learning new skills — anything from painting to music to animation. I liked the structure of the idea.

It gave a clear timeframe and created a way to measure progress, or at the very least reflect on the learning process more clearly. So I decided to try it out with drawing.

I didn’t start this with any strong expectations — the idea wasn’t to become a master at the end of 100 hours.

The goal was just to see what kind of progress could be made with consistent effort, and to document the process along the way.

Everything below was drawn during those 100 hours, from the first page to the last.

To kick things off, I started with the fundamentals of perspective. Specifically one-point and two-point constructions. The first 5 to10 hours of the challenge were spent getting familiar with how to build scenes and forms using vanishing points.

This gave me away to anchor my drawings with a stronger sense of structure, even if the sketches themselves were still rough. A lot of this early work was focused on simple shapes, boxes, and environments, just trying to train my eye to spot angles and proportions more accurately.

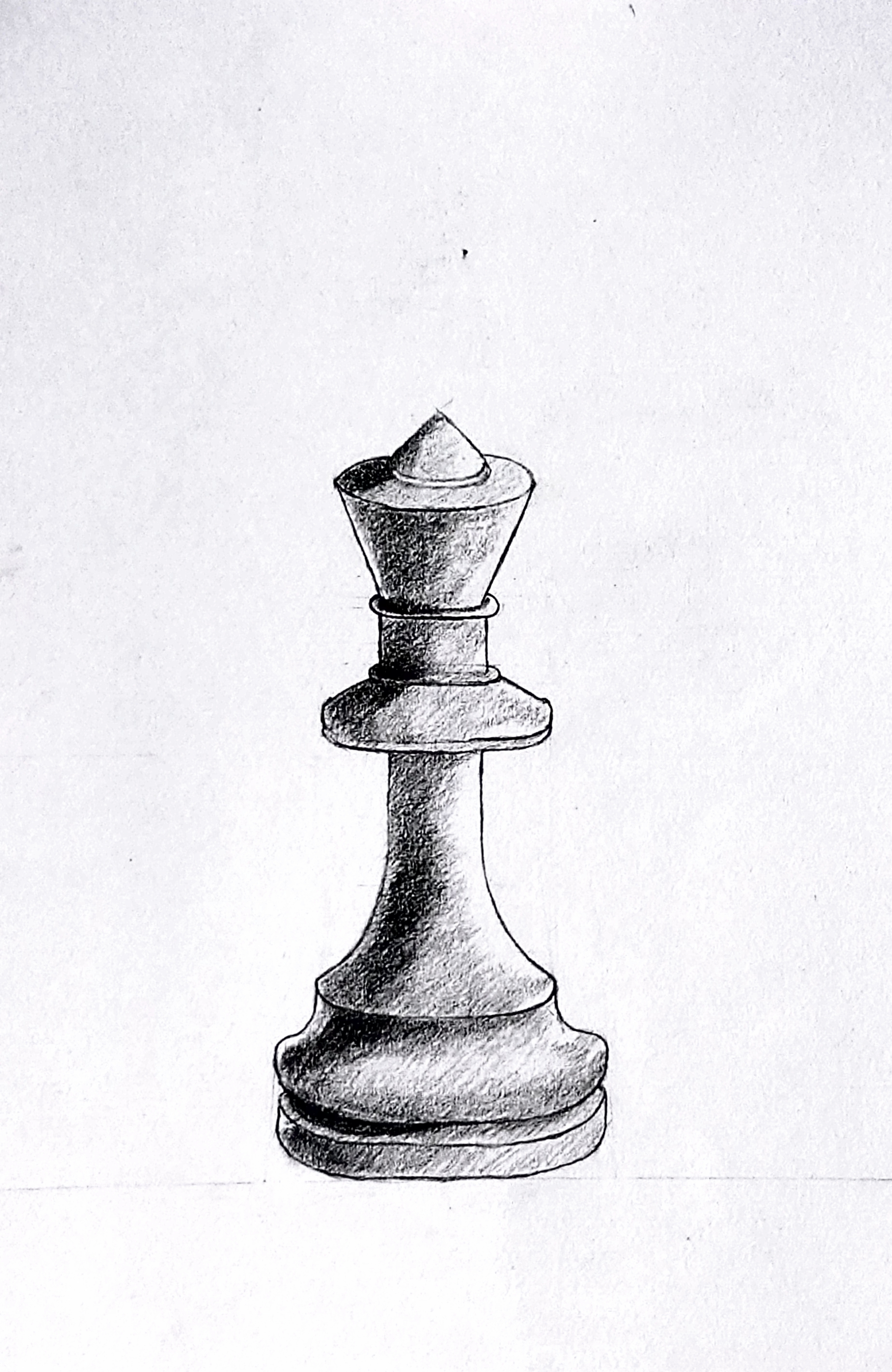

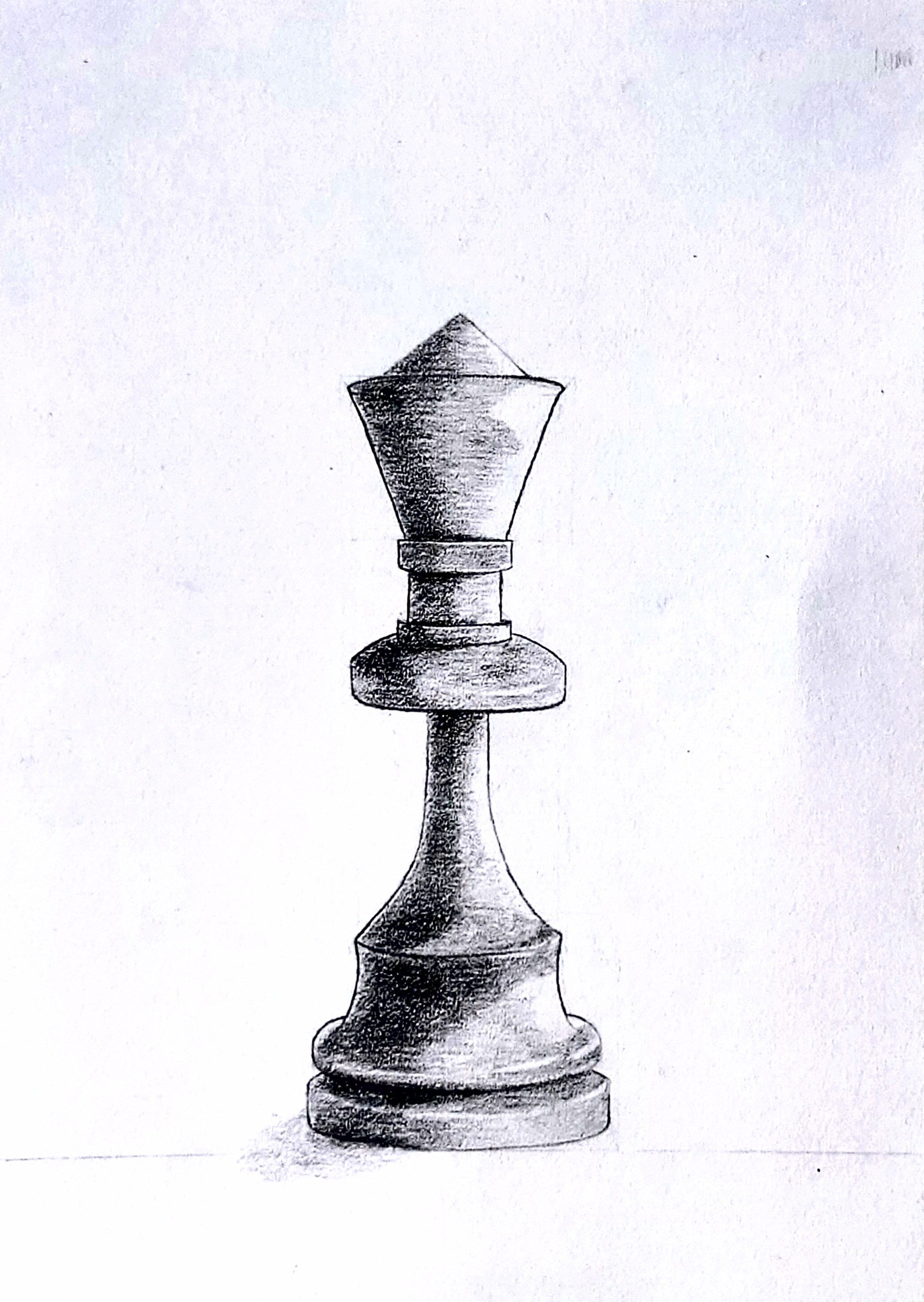

Early on, I took a small detour from the structured lessons to test how well I could translate reference into drawing form. Since I work in visual effects, I'm used to spending a lot of time looking at detailed references, which I thought might help me spot shapes and lighting a bit more easily — even if I hadn’t practiced doing it with a pencil before.

To explore that, I did a small experiment: I chose a chess piece and drew it from reference using perspective — no warm-up, just a first attempt. Then, I analysed what could be improved: proportions, lighting, shadow placement. With those notes in mind, I redrew the exact same piece. It took nearly twice as long the second time, but the result was noticeably better.

The lighting felt more grounded, the form more accurate. It was a good reminder that improvement isn’t always about more attempts — sometimes it’s about pausing to assess and correct with intention.

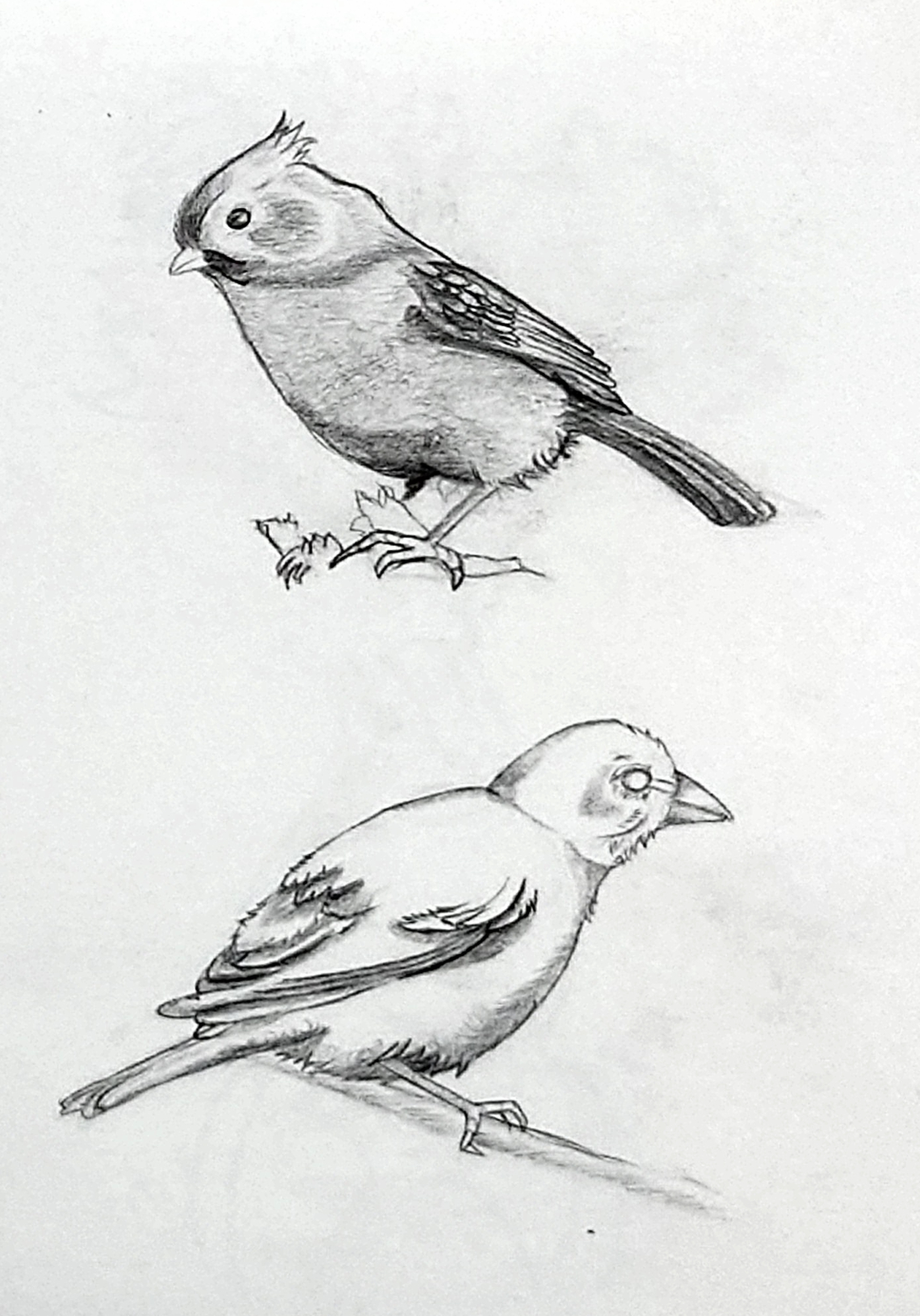

After getting a handle on perspective, I moved into using basic shapes as the foundation for constructing drawings. This meant studying a reference and identifying the underlying forms — cylinders, boxes, spheres — and paying close attention to their proportions relative to one another. I practiced this with all kinds of objects: shoes, bottles, and even birds. It was a shift in mindset from copying what I saw to constructing what I understood.

To push that further, I started doing timed sketches— usually 30-minute sessions — using the same shape-based construction method.

These timers added a new layer of learning. They forced me to think strategically: how much time should I spend laying down structure versus refining details? That balancing act became just as important as the drawing itself. In a way, this phase wasn’t just about improving the art—it was about learning how to manage the process behind it.

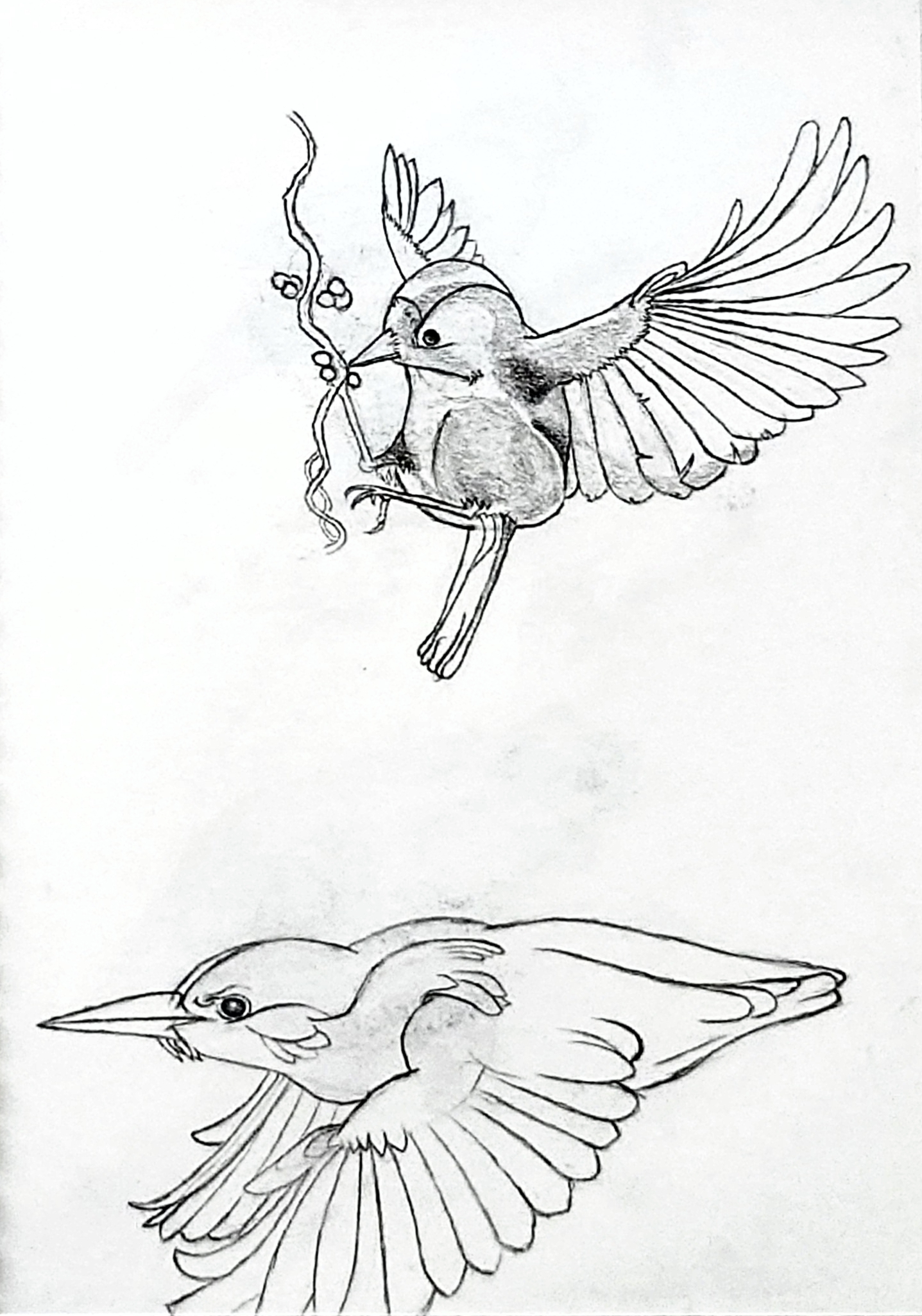

At around the 30-hour mark, I felt like I was finally starting to get a handle on drawing more consistently. Up to this point, I’d mostly been sticking with birds — they were a great way to practice flowing forms and subtle curves — but here I began pushing myself into more complex territory.

I started exploring animals with trickier anatomy: bushy tails, antlers, thicker bodies, even some basic muscle structure. It was the first time I really had to think about construction — not just copying what I saw, but understanding the shapes underneath. These drawings were slower and took more effort, but they also felt more rewarding.

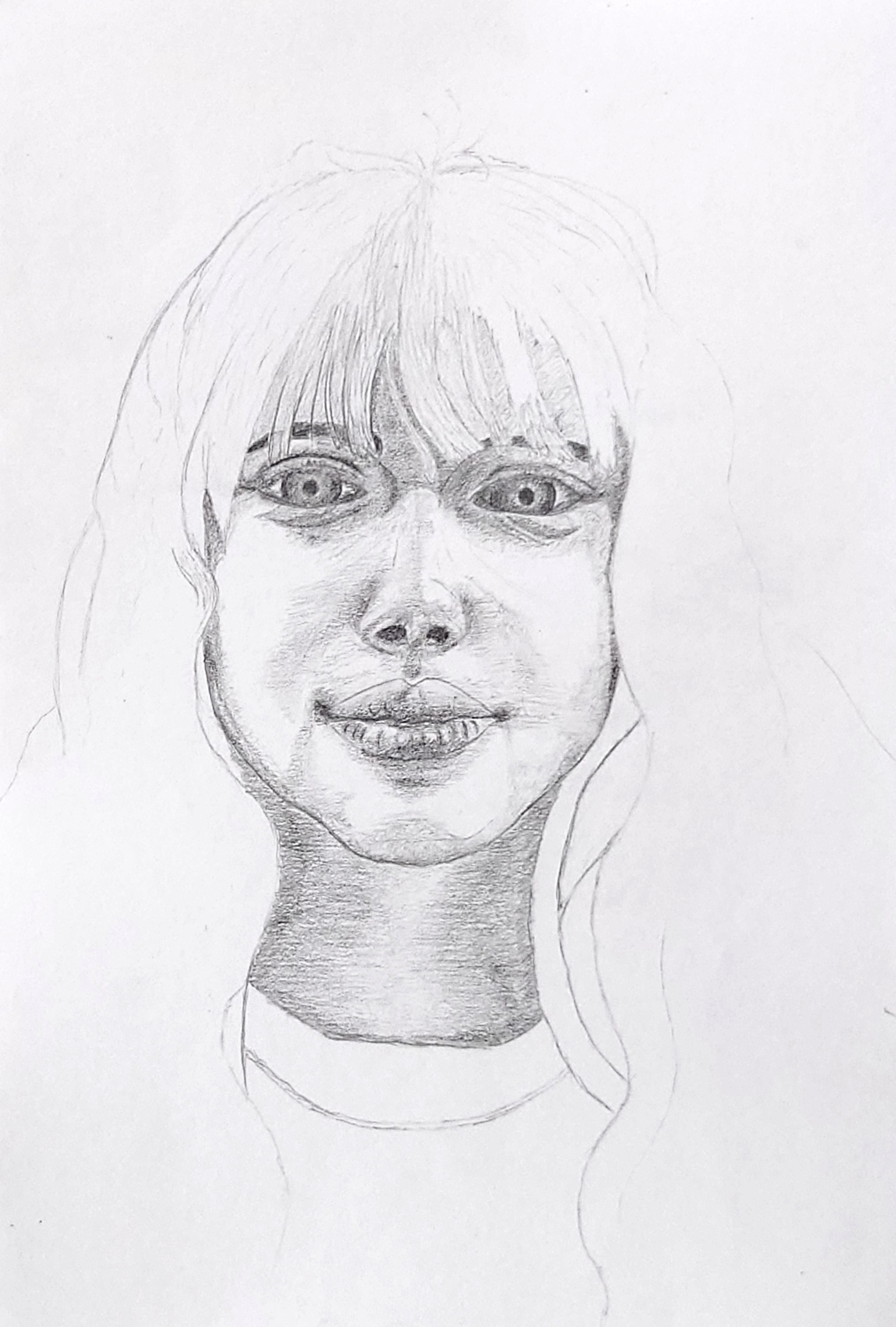

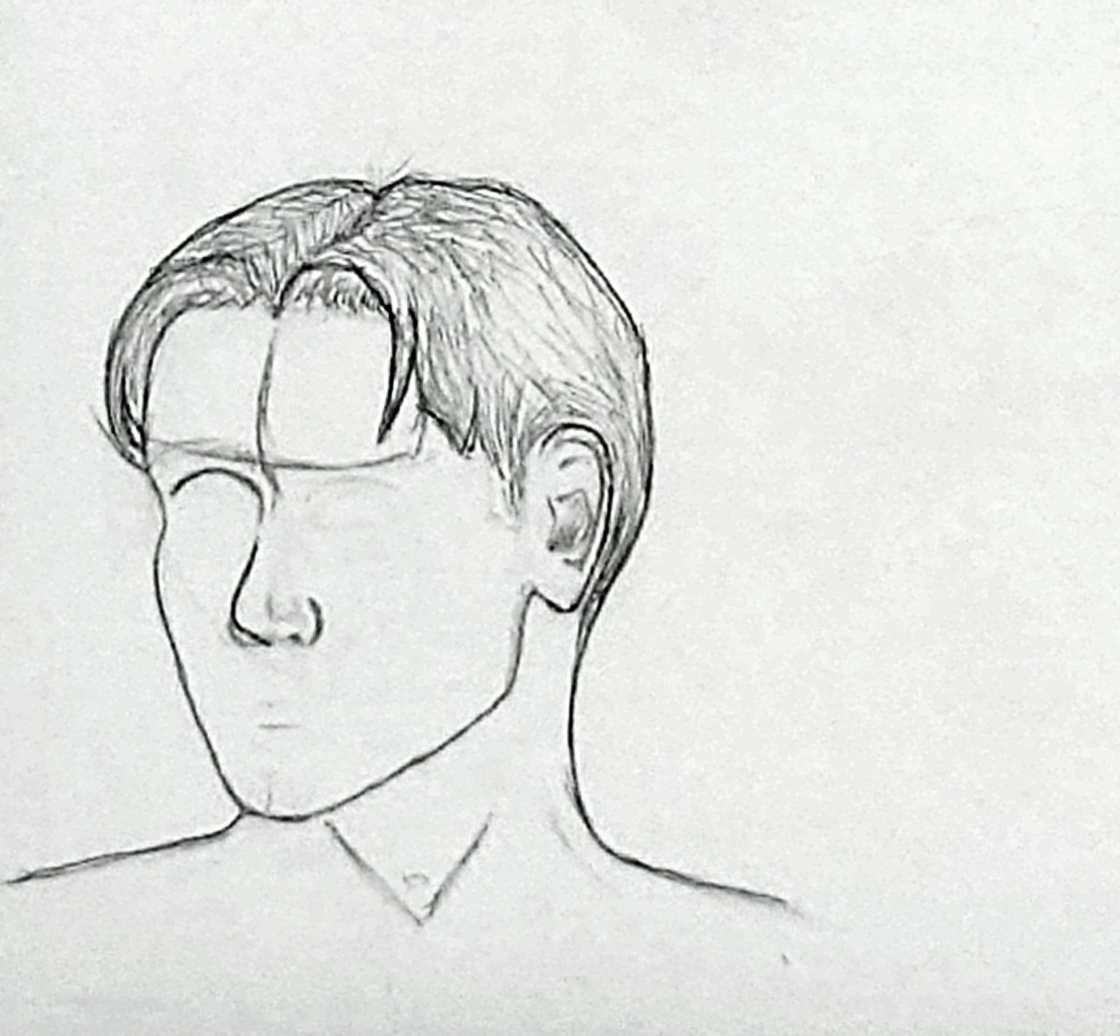

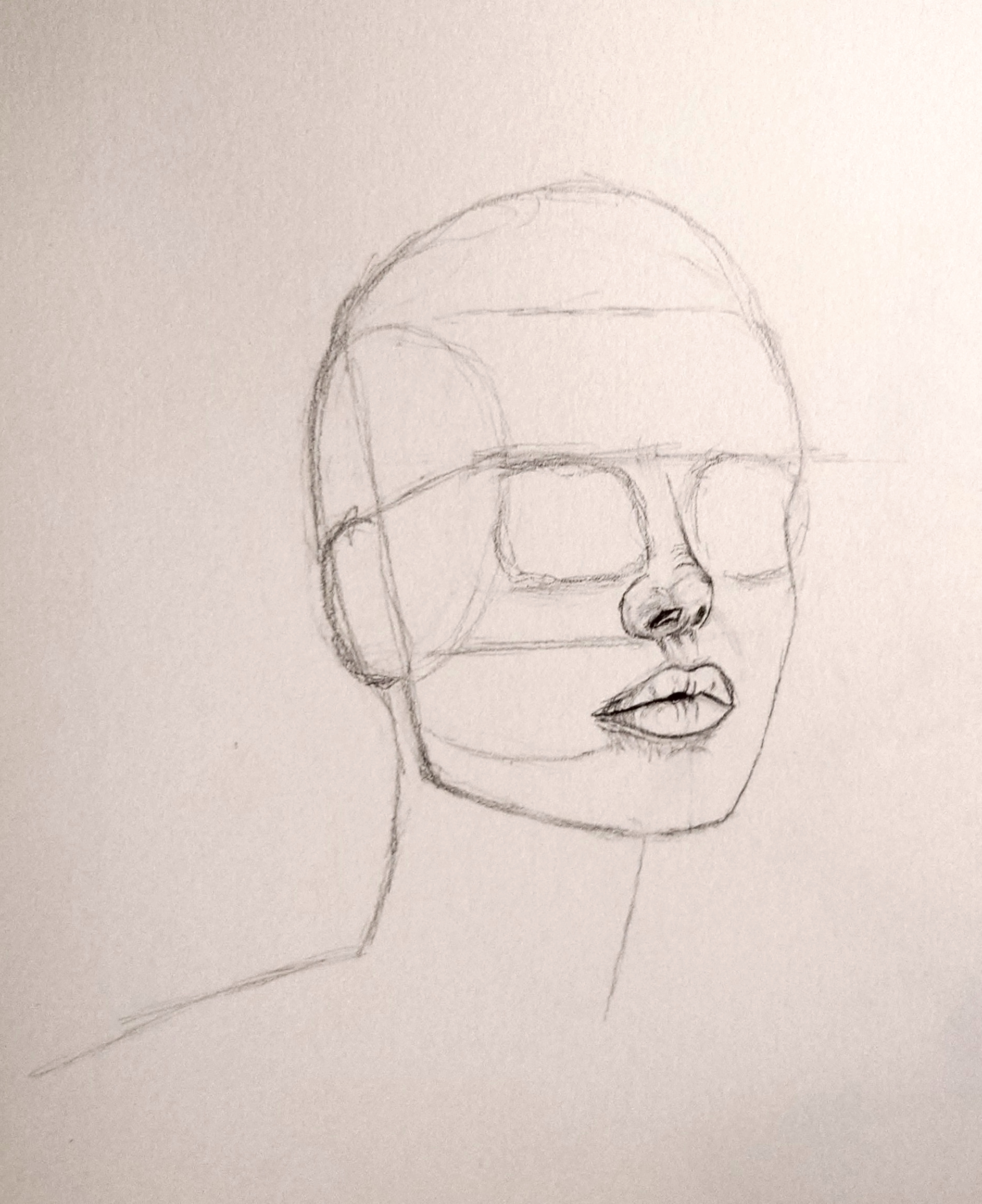

Around this point, I felt ready to challenge myself with some portrait work. I began exploring different methods, including the well-known Loomis method — a structured approach that builds the head from basic shapes and guidelines.

While it made sense in theory, I found myself struggling to move beyond the early construction lines and into fully developed portraits. It took time to find a rhythm that worked for me.

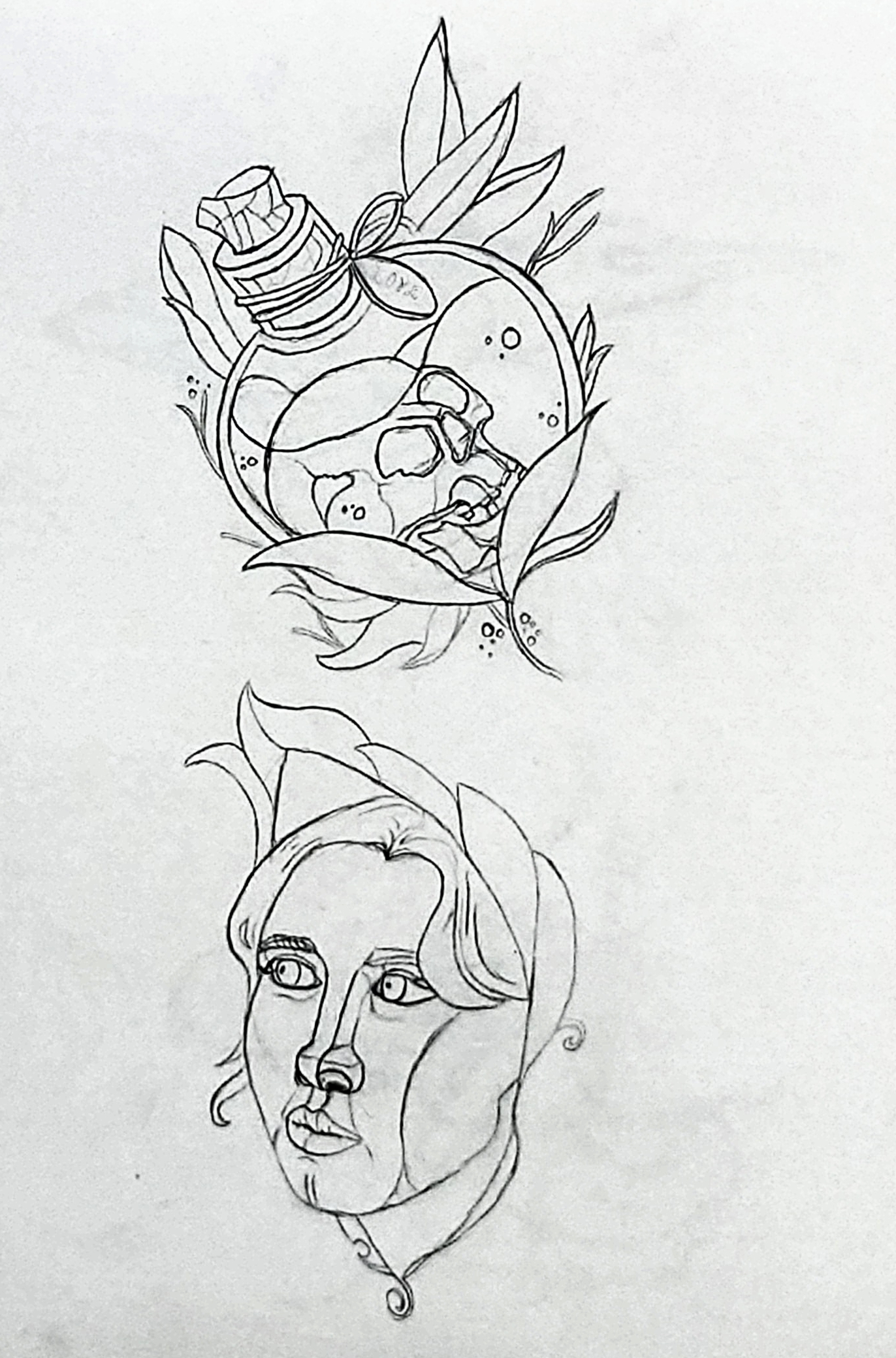

For some of the early portrait attempts —like the full-face and eyeline sketches — I leaned back on the shape identification approach I’d used with objects. Breaking the reference down into forms and contour lines gave me a way to move forward when the Loomis method felt too stiff.

I’d start with structure, then develop those lines into shaded features with a focus on proportion and placement. I also tested out the method on a drawing of a skull in a bottle.

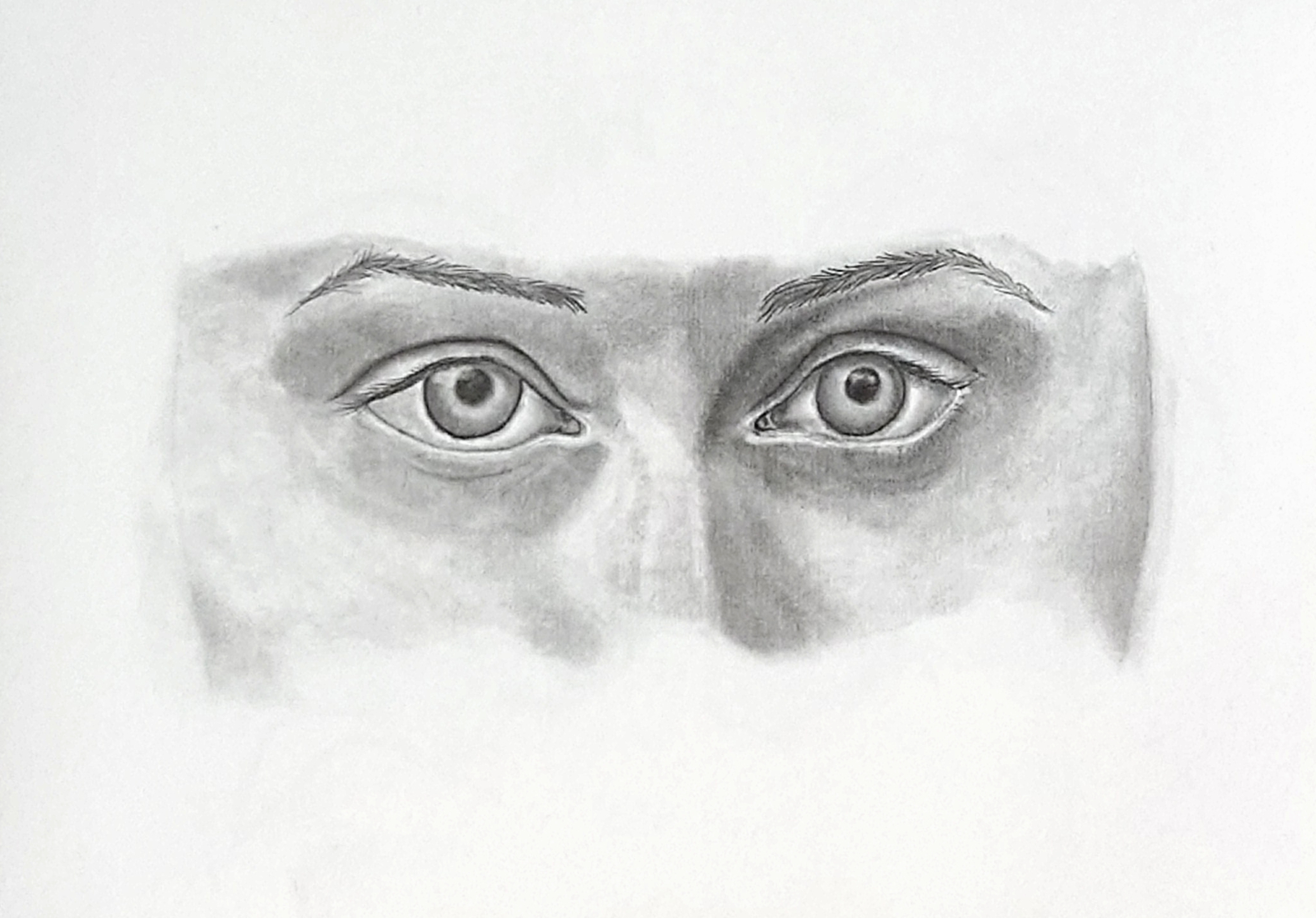

To better understand the Loomis method, I also practiced it on a smaller scale, focusing on facial features rather than whole heads. This helped me get quicker feedback from each sketch and build up a better sense of how construction lines could guide more finished forms. Even when it wasn’t clicking right away, every attempt was useful — and gradually, I started to see how the pieces fit together.

This is when the Loomis method really started to click for me. I had a solid grasp of the initial construction — the ball, cross, and jaw structure — but what helped bridge the gap was doing follow-along videos where I could watch the process unfold in real time.

There wasn’t any instruction, just observation, which forced me to pay closer attention to how the forms were being carved in from the basic Loomis head.

It trained my eye to see the transition from structure to likeness, and helped me get more confident in mapping features while maintaining construction.

This deer drawing was a real milestone piece for me. It brought together everything I’d been practicing — from construction and proportion to contour accuracy and shading. I spent around 10 hours on it, slowly building up the forms and being deliberate with how I handled light and shadow.

The biggest lesson here was learning to stay consistent with even shading across the entire piece. It taught me how subtle value shifts can bring a drawing to life when applied patiently.

Finishing this piece felt like a full-circle moment — a clear marker of how far I’d come since hour one. While there’s always more to learn, reaching the 100-hour mark gave me the confidence that deliberate, focused practice really does pay off.